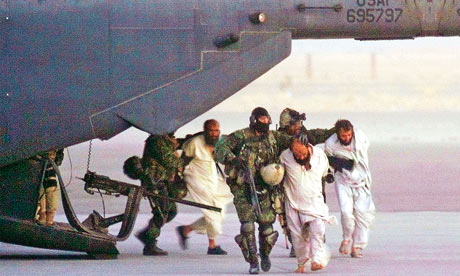

Military personnel escort detainees to a US interrogation centre at at Kandahar airport, Afghanistan. Photograph: AP

When the US and its allies went to war in Afghanistan in 2001, it was inevitable that a small number of those captured on the battlefield would be British. For more than a decade, MI5 had been aware that British Muslims had been travelling to Pakistan and Afghanistan in what it saw as a form of jihadi tourism that posed no threat to the UK. All that changed after 9/11.

Among the Britons who were picked up in the wake of the attacks was a man called Jamal al-Harith. Born Ronald Fiddler in Manchester in 1966, Harith had converted to Islam in his 20s and travelled widely in the Muslim world before arriving in Afghanistan. After 9/11, he had been imprisoned by the Taliban, who suspected him of being a British spy. At one point he and several other prisoners were forced to share their large cell with a horse that had offended a local Taliban leader in some ill-defined way. A British journalist found Harith languishing in the prison in January 2002 and alerted British diplomats in Kabul, believing they would arrange his repatriation. Instead, they arranged for him to be detained by US forces, who took him straight to an interrogation centre at Kandahar.

Harith then spent two years at Guantánamo, being kicked, punched, slapped, shackled in painful positions, subjected to extreme temperatures and deprived of sleep. He was refused adequate water supplies and fed on food with date markings 10 or 12 years old. On one occasion, he says, he was chained and severely beaten for refusing an injection. He estimates he was interrogated about 80 times, usually by Americans but sometimes by British intelligence officers.

Nine months after his release, Harith issued a statement in which he said he was still in pain as a result of the beatings he received before interrogation. "The irony is that when I was first told in Afghanistan that I would be in the custody of the Americans, I was relieved. I thought that I would then be properly dealt with and returned home without much delay."

A number of US Department of Defense documents leaked several years later showed that, like other men who were rounded up and taken toGuantánamo, Harith was there not because he was thought to be dangerous, but because the information he possessed was considered useful. Harith's file shows that he was sent to Guantánamo "because he was expected to have knowledge of Taliban treatment of prisoners and interrogation tactics". Eighteen months later, the camp authorities had satisfied themselves that he had no connection with the Taliban or al-Qaida, but decided against releasing him because his "timeline has not been fully established" and because British diplomats who had seen him in Kandahar had found him to be "cocky and evasive".

In all, nine British nationals were sent to the maximum-security prison at Guantánamo, along with at least nine former British residents. All were incarcerated for years, and from the moment they arrived they suffered beatings, threats and sleep deprivation. All were interrogated by MI5 officers and some also by MI6. When Harith was eventually released, along with three men from the West Midlands known as the Tipton Three, a man called Martin from the Foreign Office was waiting for them as they boarded the plane home. "Can you," he asked, "make sure you say you were treated properly?"

Martin's boss, foreign secretary Jack Straw, was particularly concerned that the wider world should never learn of the extent to which the British government had become involved in the torture of its own citizens at Guantánamo. In December 2005, the full truth about British complicity in rendition and torture was still such a deeply buried official secret that Jack Straw felt able to reassure MPs on the Commons foreign affairs committee about the allegations starting to surface in the media. "Unless we all start to believe in conspiracy theories," he said, "and that the officials are lying, that I am lying, that behind this there is some kind of secret state which is in league with some dark forces in the United States… there simply is no truth in the claims that the United Kingdom has been involved in rendition."

Two days after 9/11, during a meeting of President Bush's closest advisers, his head of counter-terrorism, Cofer Black, declared the country's enemies must be left with "flies walking across their eyeballs". Unlike its allies – the UK, France, Spain and Israel – the US had little experience of serious terrorist attacks on its own territory. Bush turned to his Department of Defense and found it had no cogent, off-the-shelf plan for a response. The CIA, on the other hand, did have something in its arsenal: it had the rendition programme.

Since 1987, the CIA had been quietly apprehending terrorists and "rendering" them to the US for prosecution, without any regard for lawful extradition processes. In 1995, President Bill Clinton – apparently with the full encouragement of his vice-president, Al Gore – agreed that a number of terrorists could be taken to a third country, including countries known to use torture, a process that would come to be known as extraordinary rendition.

Within five days of 9/11, Black had drawn up plans for the CIA's response. It would entail a vast expansion of the rendition programme. Hundreds of al-Qaida suspects would be tracked down and abducted from their homes and hiding places in 80 different countries. The agency would decide who was to be killed and who was to be kept alive in a network of secret prisons, outside the US, where they would be systematically tormented until every one of their secrets had been delivered up.

The evening before Bush signed off the plans, Black and a handful of other senior CIA officers went to the British embassy in Washington, where they told senior British intelligence officers what was about to happen. At the end of Black's three-hour presentation, his opposite number at MI6, Mark Allen, commented drily that it all sounded "rather blood-curdling". Allen also expressed concern that once the Americans had "hammered the mercury in Afghanistan", al-Qaida would simply scatter across south Asia and the Middle East, destabilising entire regions. One of the CIA officers at the meeting, Tyler Drumheller, could see that while the British appeared laid-back, "it was clear they were worried, and not without reason". According to one account, even Black joked that one day they might all be prosecuted.

Shortly afterwards, Allen departed for London, where Tony Blair and Jack Straw were waiting to be briefed on the Americans' plans. The CIA's closest ally had been put on notice: the British could never honestly claim that they did not know what was about to unfold.

At the end of September 2001, the United Nations Security Council passed resolution 1373, which required member states to do more to assist the US and each other in eliminating international terrorism. On 2 October, Nato members met at the organisation's headquarters in Brussels and agreed they should invoke article five of the North Atlantic Treaty, under which an attack on one member is to be regarded as an attack on all. At a second meeting two days later, the US representatives presented a number of specific requests, all of which were granted. Eight of those requests have since been made public. They included enhanced intelligence sharing, taking "necessary measures to increase security" and granting blanket over-flight clearances for the US and other allies' aircraft for military flights engaged in counter-terrorism operations. Nato has since admitted that a number of other requests were granted; all of them remain secret.

Over the next few years, men were rendered not only from the war zones of Afghanistan and Iraq, but from Kenya, Pakistan, Indonesia, Somalia, Bosnia, Croatia, Albania, Gambia, Zambia, Thailand and the US itself. The US was running a global kidnapping programme on the basis of Black's plan and the agreements reached at the Nato meeting. Some prisoners were dispatched to Middle Eastern countries, including Jordan and Syria, or to Afghanistan and Uzbekistan, and an unknown number were sent to secret prisons that the CIA operated in Thailand, Poland, Lithuania and Romania. Wherever they ended up, they had one thing in common: they were going to be tortured.

Quietly, Britain pledged logistics support for the rendition programme, which resulted in the CIA's Gulfstream V and other jets becoming frequent visitors to British airports en route to the agency's secret prisons. Over the next four years, a 26-strong flight of rendition aircraft operated by the CIA used UK airports at least 210 times. Dozens of private executive jets chartered by the agency were also regular visitors to the UK.

A US military guard patrols cells that can be watched from above at Parwan detention centre near Bagram airbase. Photograph: AP

A US military guard patrols cells that can be watched from above at Parwan detention centre near Bagram airbase. Photograph: APThe US authorities also asked the UK for permission to build a large prison on Diego Garcia, the British territory in the Indian Ocean that operates as a US military base. The project was dropped, for logistical rather than legal reasons, but Diego Garcia continued to be used as a stopover for rendition flights, and senior UN officials believe that a number of prisoners were held and interrogated there in 2002 and 2003.

The UK would do more than offer mere logistics support to the rendition programme, however. It would become an enthusiastic participant. And, as I discovered, this would not be the first time it was involved with the torture of its own citizens.

In 2005, when I was investigating the UK's support for the US rendition programme, two words in a book review caught my eye. The article referred to a wartime detention centre I'd never heard of: the London Cage.

An out-of-print book led to some yellowing cuttings at the British Library, which in turn led to a handful of declassified files at the National Archivesin Kew. Freedom of Information requests led to more government files being reluctantly handed over, and I began to learn more about the torture centre that the British military had operated throughout the 1940s, in complete secrecy, in a row of Victorian villas in one of the most exclusive neighbourhoods in London. During the course of the war, thousands of Germans had been beaten, deprived of sleep and forced to assume stress positions for days at a time. But many of the first to arrive at this interrogation centre were not Germans but British fascists. The interrogation of British nationals all but ended in November 1940, but the centre continued to operate for more than three years after the end of the war.

The files at the National Archives also contained a couple of oblique references to another interrogation centre that the British had run during the cold war, this time in the village of Bad Nenndorf, near Hanover. The taking of life there was not unknown. There were further hints in the files that other such facilities may have existed, not just in postwar Germany, but also in north Africa, the Middle East and beyond. Throughout the postwar period, it seemed, there had been a network of secret prisons, hidden from the Red Cross, where men thought to pose a threat to the state could be kept for years and systematically tormented. And what of more recent incidences?

Why had the British army in Northern Ireland resorted so readily to torture on the opening day of internment in August 1971, and how did they develop the interrogation methods – the so-called five techniques – that they employed? Why, long after the Troubles in Northern Ireland had ceased to resemble civil war, had coercive interrogations remained at the heart of the UK's counter-terrorism strategy, being used to extract confessions from hundreds of suspected paramilitaries who could then be convicted by the no-jury courts?

There were also the former British colonies. In the early 21st century, a group of ageing former Mau Mau fighters started proceedings against the British government, alleging that they had been systematically tortured in prison camps in Kenya in the 1950s. Their claims were resisted every step of the way, and earlier this month, when they finally won permission to sue the government, the Foreign Office said it would appeal, despite having admitted that the allegations were entirely true.

None of this squares with Britain's reputation as a nation that prides itself on its love of fair play and respect for the rule of law. Surely the British avoid torture, if only because it is British to do so?

Around this time, I arranged to see a man who knows something of the darker workings of Britain's secret state and who, from time to time, has helped me with my inquiries. I met this man – let's call him James – at a cafe near Liverpool Street station. After studying the couple at the next table for a moment, he asked two questions that went far beyond those I'd been willing to ask myself: "Do you think it's possible that the British government has a secret torture policy, one that it's determined nobody should ever know about? And if so, do you think it's possible that responsibility for that policy goes right to the very top?"

Back in London in 2001, government ministers and their intelligence advisers could not decide what to do with the young British Muslims being interrogated at Kandahar and at a second centre that US forces had established at Bagram airbase north of Kabul. One idea was to have them brought back to the UK and prosecuted, possibly for treason. MI5 asked the Crown Prosecution Service whether they could "interview" the prisoners first and were told they could, as this would not inhibit any subsequent prosecutions.

In Washington, meanwhile, members of Bush's war cabinet had decided that the expanded rendition programme should result in the majority of prisoners being interrogated by the US military, rather than by overseas intelligence agencies. They needed somewhere to carry out these interrogations and chose the Guantánamo Bay naval base on Cuba as the site for Camp X-Ray. On 6 January 2002, the first US combat engineers and contractors arrived at Guantánamo to begin construction. Three days later, senior lawyers at the US justice department drafted a memo that concluded that the Geneva conventions did not apply to al-Qaida fighters or Taliban members.

Twenty-four hours after the drafting of this memo, on 10 January, British ministers had second thoughts about prosecuting British Muslims captured in Afghanistan. Government lawyers were warning that these men appeared not to have committed any offence under UK law and there was deep anxiety that the US government would be furious if they were brought back to the UK and subsequently released. Furthermore, police interviews in the UK would not be so effective as interrogations conducted overseas. So ministers decided, in the words of a secret Foreign Office memorandum, that their "preferred option" was the rendition of British nationals to Guantánamo.

Events moved rapidly. Later that day, Straw issued a classified telegram to the British embassy in Washington and embassies across the Middle East: no objection should be raised to the transfer of the British nationals to Guantánamo, he ordered, as this was "the best way to meet our counter-terrorism objectives". He added, however, that their removal from Afghanistan should be delayed long enough to allow questioning by a "specialist team" of MI5 interrogators.

The first team of MI5 interrogators had arrived in Afghanistan the previous day, joining a number of MI6 officers who had entered the country at the end of 2001. The first interrogation was conducted at Bagram just as Straw was sending his telegram. There were 80-odd prisoners there, mostly Afghans and Arab fighters, and a handful of Britons, and it was immediately obvious they were being mistreated. Some of the prisoners were chained upright inside the pens with hoods over their heads. Others were being beaten. One of the officers alerted his superiors that the first prisoner he questioned had been abused by the US military before the session began, and the complaint was passed rapidly back to London.

The next day, both MI6 and MI5 sent written guidance to all of their officers in Afghanistan. Covering two pages, these instructions had been prepared earlier in anticipation of such a complaint and were very carefully crafted. Referring to the treatment of the prisoners, the guidance stated that: "Given that they are not within our custody or control, the law does not require you to intervene to prevent this. That said, HMG's stated commitment to human rights makes it important that the Americans understand that we cannot be party to such ill-treatment nor can we be seen to condone it." It continued: "It is important that you do not engage in any activity yourself that involves inhumane or degrading treatment of prisoners."

So MI5 and MI6 officers should not be seen to condone torture and must certainly not torture any prisoners themselves. But, crucially, they could continue to question people whom they knew were being tortured. The door that could have been shut upon the use of torture had been left open just a crack, and over the years to come, all manner of horrors would slip quietly through.

At least two Afghans died under interrogation at Bagram after being chained for several days from the ceiling of their cells while being beaten about the legs. Postmortem examinations showed their injuries were so severe that, had they survived, their legs would have had to be amputated.

There are allegations that British intelligence officers witnessed the abuse at Bagram and even took part. Shaker Aamer, a Saudi who lived in London before travelling to Afghanistan, has given a statement to one of his lawyers in which he says British intelligence officers were present while Americans beat him and smashed his head against a wall.Moazzam Begg, from Birmingham, says he spoke not only to British intelligence officers at Bagram, but to visiting British soldiers.

On 14 January 2002, four days after Straw sent his secret rendition telegram, a senior official attached to the Cabinet Office sent a six-page memo to David Manning, Tony Blair's foreign policy adviser, naming three British citizens held in Afghanistan and noting that they were "possibly being tortured" at a jail in Kabul. By 18 January, at the latest, Blair had been made aware.

The prime minister wrote by hand in the margins of one Foreign Office memo: "The key is to find out how they are being treated. Though I was initially sceptical about claims of torture, we must make it clear to the US that any such action would be totally unacceptable." Blair added a curious instruction to his officials: not to endeavour to stop the torture, but to "v quickly establish that it isn't happening".

Despite the prime minister being made aware of the possible use of torture, the UK remained a committed partner in the rendition programme. All but two of the British citizens and residents who ended up in Guantánamo were sent there after Blair wrote his note. Documents later disclosed in court showed that after one British terrorism suspect,Martin Mubanga, was detained in Zambia, either Blair or someone close to him at Downing Street intervened to ensure that he could not escape rendition to Guantánamo. Mubanga denied any involvement in terrorism. Nevertheless, a reason for his rendition was set out in a note that Eliza Manningham-Buller of MI5 sent to John Gieve, the permanent secretary at the Home Office, which was also disclosed in court: "We are… faced with the prospect… of the return of a British citizen to the UK about whom we have serious concerns, whom it may be difficult to prosecute and whose release could trigger hostile US reaction."

Binyam Mohamed arrives at Northolt after his release from Guantánamo. Photograph: PA

Binyam Mohamed arrives at Northolt after his release from Guantánamo. Photograph: PAMI5 and MI6 officers carried out around 100 interrogations at Guantánamo between early 2002 and the end of 2004. Even when British intelligence officers weren't present in the room, their input in the interrogation of prisoners with a British connection was often vital, as it was in the case of Binyam Mohamed, a 23-year-old Ethiopian who had been living in London. Details of what happened to Mohamed would emerge piece by piece during civil proceedings that were later brought on his behalf in the British courts. It was a textbook example of complicity in torture, one that would result in MI5 facing a criminal investigation for the first time in its history.

In April 2002, Abu Zubaydah, a Saudi militant suspected of being a senior al-Qaida figure, was interviewed by FBI agents. He told them of two men who had been tasked with mounting an operation almost as ambitious as the attacks of 9/11: the detonation of a radiological dispersal device, or dirty bomb, in an American city. One of the two men was identified as "Binyamin Mohamed", who had been detained in Karachi while attempting to board a flight to London with a doctored passport. Mohamed denies he is a terrorist and, despite having clear reason to regard him as suspicious, US authorities would later admit that the dirty bomb plot never proceeded beyond some rudimentary internet research.

Mohamed was handed over for brutal interrogation. The Pakistanis and Americans soon established that he had been living in London before travelling to Afghanistan, and MI5 and Scotland Yard's special branch began questioning his friends and associates in west London. The following month, the CIA granted the British permission to question Mohamed.

When the court discovered that MI5 and MI6 knew full well that Mohamed had been tortured before the British officer was sent to question him, the British government attempted to persuade the judges to omit this fact from their public judgments. David Miliband, then foreign secretary, was particularly anxious to preserve the control principle in relation to intelligence, whereby material provided by one nation to another could not be released without the consent of the originating country. Under this heading, he argued that the public should not learn of seven key paragraphs from one court judgment that revealed that MI5 were aware that Mohamed had been "intentionally subjected to continuous sleep deprivation" and that the effects of the sleep deprivation were "carefully observed"; that Mohamed was told he could be made to disappear; and that the interrogation and mistreatment were causing "significant mental stress and suffering".

While the British officer said nothing in court about his prior knowledge of Mohamed's torture, he did let slip one intriguing fact. He explained that he served with a division of MI5 known as the "international terrorism-related agent running section": the section routinely responsible for interviewing suspected terrorists. The MI5 officers who were interrogating al-Qaida suspects – men who were being tortured in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Guantánamo and elsewhere around the world – were agent handlers. It appeared that MI5 was seeking to recruit torture victims as double agents.

Mohamed was rendered to a secret prison near Rabat in Morocco, where interrogators beat him for hours and subjected him to loud noise for days. Once a month, he says, his torturers used scalpels to make shallow, inch-long incisions on his chest and genitals. He was accused of being a senior al-Qaida terrorist. Mohamed says he would say whatever he thought his captors wanted and he signed a statement about the dirty bomb plot.

It was clear that Mohamed was being interrogated, in part, on the basis of information supplied by the UK. During the subsequent court case, it would emerge that reports of what Mohamed was saying under torture also flowed back to London. The security service's lawyers admitted that MI5 knew Mohamed was not in US custody during this period, but repeatedly denied knowing he was being held in Morocco. Then a number of documents disclosed during the case showed that the British officer had visited the Moroccan torture centre on three occasions while Mohamed was being tortured there. After the last visit, MI5 had sent the CIA a list of 70 questions that it wanted put to Mohamed.

Mohamed's torture in Morocco went on for 18 months until a team of masked Americans came to take him away. One photographed his genitals, to establish that they had been mutilated when he was with the Moroccans, not in US custody. Then it was off to Afghanistan. For five months he was detained in a darkened cell in a prison somewhere near Kabul. He says he was chained, subjected to loud music and questioned by Americans. Four months later he was flown to Guantánamo, where he says he was routinely humiliated and abused over the next four and a half years.

Mohamed became one of the best-known victims of rendition and torture after 9/11, and one of the most blatant examples of British complicity in US crimes. But he was far from alone and he would not be the last.

Within two months of the May 2010 general election, under pressure from his Liberal Democrat coalition partners, as well as some of his own backbenchers, the new prime minister, David Cameron, announced the establishment of a judge-led inquiry into the UK's involvement in torture and rendition. In July 2010, the man appointed to head the inquiry was named as Sir Peter Gibson, a retired judge. It is possible that MI5 and MI6 had a hand in his selection; certainly they could not have hoped for a better choice: for the previous four years Gibson had served as the intelligence services commissioner. Mohamed's lawyers suggested that Gibson should be appearing before the inquiry as a witness rather than presiding over it.

In July 2011, most major international and British human rights groups, including Amnesty International, said they would be boycotting the inquiry. The following month, lawyers representing victims of Britain's torture operations announced that they, too, would have nothing to do with it. Six months later, the government gave up and announced that the Gibson inquiry was being scrapped.

Instead, the coalition moved forward with plans to change the law in a way that would prevent evidence of complicity in torture being aired in the courts in the future. It brought forward a green paper that suggested a need for greater courtroom secrecy and also proposed to abolish the legal doctrines that had been employed by Mohamed's lawyers. It looked like Britain's complicity in torture was to continue to be a dirty little secret.

• This is an edited extract from Cruel Britannia: A Secret History Of Torture, by Ian Cobain, published next month by Portobello Books at £18.99. To order a copy for £15.19, with free UK mainland p&p, go toguardian.co.uk/bookshop or call 0330 333 6846.

No comments:

Post a Comment