Canberra lawyer to trek Ethiopia's Simien Mountains in support of UNICEF child protection: "Canberra lawyer to trek Ethiopia's Simien Mountains in support of UNICEF child protection

Date

September 28, 2015 - 11:30PM

Read later

Clare Sibthorpe

Canberra Times reporter

View more articles from Clare Sibthorpe

Follow Clare on Twitter Email Clare

inShare

submit to redditEmail articlePrint

Canberra lawyer Brodie Williams is trekking in Ethiopia in support of UNICEF's child justice programs. Photo: Rohan Thomson

Canberra solicitor Brodie Williams has personally raised more than $8000 for UNICEF's child justice programs to trek the incredibly challenging Simien Mountains, alongside armed protection and medical assistance.

Almost 50 DLA Piper Global Law Firm staff (just six from Australia), will set off on October 2 to attempt the six day hike to 4430 metres above sea level, walking up to ten hours a day.

"We'll have two doctors with us because altitude affects you at about 3000 metres and we're going up even higher than that... and the terrain is really rocky and steep and off the trail so there's no path or anything," Ms Williams explained.

"We also have two armed riflemen coming with us because apparently there's a lot of vicious wildlife."

Advertisement

DLA Piper, a global partner with UNICEF, has pledged to raise $1.5 million in cash over five years and support them with $5 million of Pro Bono assistance. The funds will help UNICEF protect children in Bangladesh who come into contact with the law. It's a cause close to Ms Williams' heart, as she's been working on projects that support research into child marriage – a common practice in Bangladesh.

"Unfortunately it's happening to children as young as five, it's so sad," Ms Williams said.

"I've got the best family in the world and I value that more than anything and that's why I think what UNICEF is doing is so important, because these children don't have that tight unit. They are married off into someone else's family and often these people don't care and it's not a love relationship, it's a commercial transaction."

While acknowledging she's about to embark on a life-changing experience, she said the sheer generosity and support the community has shown throughout her preparation has already changed her life.

Individual friends donated up to $300 each, her colleagues continually bought lunches she cooked, and she raised thousand of dollars at an African fashion show her firm helped her organise.

"It's restored my faith in humanity."

She said the regular training of walking, running, weight training and Bikram yoga have forced her to make time for herself amidst working extremely long hours. On weekends she's been enduring six hour treks on either one day or both days, allowing for a lot of introspection and mindfulness.

"I'm so grateful for the friends who've been willing to come trekking with me... I'm really outdoorsy but this is something completely different for me.

And I'm fitter and healthier than I've ever been."

'via Blog this'

Monday, September 28, 2015

Sunday, September 27, 2015

Ethiopian refugee begged to return home before fatal police encounter - San Francisco Chronicle

By Rachel Swan

Photo: Sarah Rice, Special To The Chronicle

From right, Annick Seri, Nadege Nadege, Meheret Anulo, and Pineal Anulo listen at a candlelight vigil for Yonas Alehegne, an Ethiopian immigrant who was shot and killed by an Oakland police officer in August, in Oakland, Calif., on Sunday, September 13, 2015.

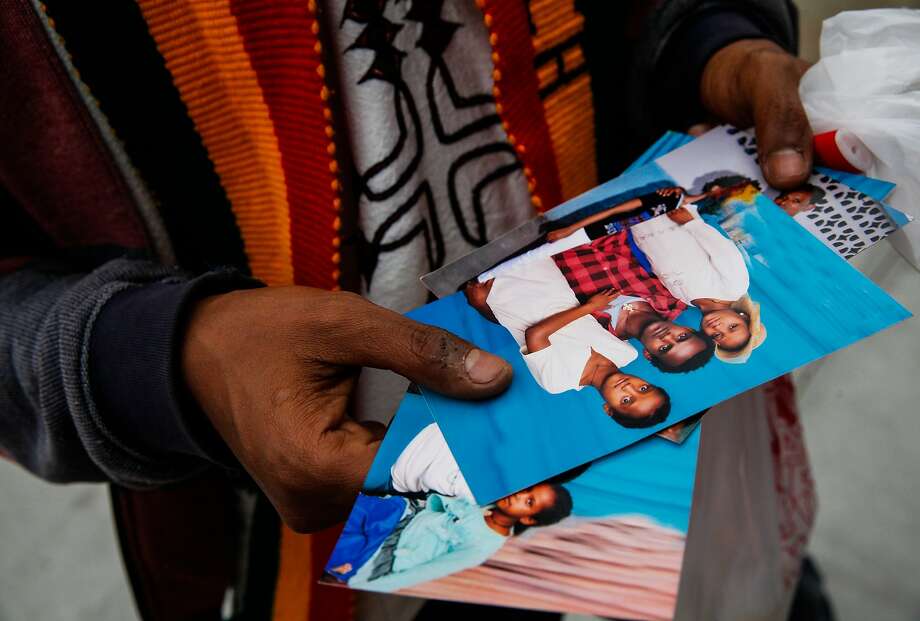

A man shot and killed by an Oakland police officer in August left behind only a small pile of luggage and a few family photographs, one of which had a phone number scrawled on the back.

The number belonged to the 30-year-old man’s mother, Genet Alemu, who sells injera bread to support a family of seven in Ethiopia. She last heard from her son, Yonas Alehegne, several months before his death.

“I feel like I’m dead,” Alemu said from her village in Dire Dawa, where she lives in a house that her other son, Habtamu, describes as “almost a tent.” Alemu was reached by phone Sept. 12 — the day of the Ethiopian new year. Dawn had broken and a rooster crowed insistently in the background.

Remembering “Yonas,” Alemu wailed.

“He was my first son,” she said, speaking through an interpreter in Amharic, the language spoken in Ethiopia. “He came to the U.S. to help us.”

Whatever dreams and ambitions Alehegne had when he arrived in the United States in 2012 were soon replaced by distress and desperation.

Photo: Sarah Rice, Special To The Chronicle

Image2of8

Rebecca Lakew, second from left, and others pray at a candlelight vigil for Yonas Alehegne, an Ethiopian immigrant who was shot and killed by an Oakland police officer in August, in Oakland, Calif., on Sunday, September 13, 2015. Lakew was working at the Ethiopian Community Center when Alehegne came in for help. Alhegne was homeless at the time he was killed.

IMAGE 7 OF 8

Nadege Nadege listens at a candlelight vigil for Yonas Alehegne, an Ethiopian immigrant who was shot and killed by an Oakland police officer in August, in Oakland, Calif., on Sunday, September 13, 2015.

African refugee

A refugee from political persecution in his home country, Alehegne hoped to find better employment and a means to send remittances back home. But, once here, he exhibited signs of mental illness, and apparently never got treatment. Interviews with family in Ethiopia, people who knew him in the United States and a review of his criminal record and probation report reveal a man who behaved in bizarre and violent ways, became homeless, got into criminal trouble and grew alienated from the systems that might have helped. Toward the end, he desperately wanted to return to Africa.

On Aug. 27, Alehegne was shot dead by Officer Jennifer Farrell on the 200 block of MacArthur Boulevard, after police say he bludgeoned her with a metal chain. He had been sleeping in the laundry room of an apartment complex, and Farrell had been called to investigate reports that Alehegne had assaulted a resident in the building’s garage. Farrell confronted Alehegne when he stepped into the street in front of her police car. When she got out of her car, police say, he struck her with the chain.

Farrell fired several shots, killing Alehegne.

“I knew it was him before they told me,” said Rebecca Lakew, a former office manager at the Ethiopian Community Cultural Center, an Oakland organization that Alehegne would often visit, asking for money and food and begging for help so that he could return home to Ethiopia.

Lakew said the center offered to buy Alehegne a plane ticket home, shortly before his death. But he never filled out the necessary paperwork.

Photo: Sarah Rice, Special To The Chronicle

Rebecca Lakew speaks at a candlelight vigil for Yonas Alehegne, an Ethiopian immigrant who was shot and killed by an Oakland police officer in August, in Oakland, Calif., on Sunday, September 13, 2015. Lakew was working at the Ethiopian Community Center when Alehegne came in for help. Alhegne was homeless at the time he was killed.

“We tried our best,” she said. “Maybe we should have tried harder.”

While some worry that the Ethiopian community failed Alehegne, others say the U.S. government should have done more to help him.

“He would have been saved if he had received proper treatment and medications,” said Tadios Belay, executive director of the Horn of Africa Human Rights Network. Belay helped set up aGoFundMe page to raise money to send Alehegne’s body back to Ethiopia and pay for funeral expenses. He is seeking the power of attorney to file a wrongful death suit against Oakland police, on behalf of Alehegne’s family.

Seeking a way out

Born to a father who served as a soldier for the Derg, a communist regime that ruled Ethiopia until 1987, Alehegne dropped out of school after seventh grade to become a day laborer, according to his brother Habtamu, who spoke to The Chronicle by phone from Ethiopia through an interpreter. Unable to find consistent work, and denied opportunities because his tribe, the Amhara, was an ethnic minority in the region, Alehegne fled Ethiopia for neighboring Djibouti when he was 18 or 19.

Alehegne left his home city of Dire Dawa on foot and walked across the border to a refugee camp, Habtamu said, traveling a distance of some 150 miles. He told family members he was assaulted along the way, claiming that strangers bit him.

Photo: Sarah Rice, Special To The Chronicle

Fikre Atnafe looks through photos of the family of Yonas Alehegne, an Ethiopian immigrant who was shot and killed by an Oakland police officer in August, at a candlelight vigil for him in Oakland, Calif., on Sunday, September 13, 2015.

“When he was at home, he was fine,” Habtamu said, adding that the journey left Alehegne traumatized. When he called home, Habtamu said, “he would ask me to pray for him.”

The U.S. State Department admitted Alehegne into the United States in 2012 under stepped up efforts by the Obama administration to increase the number of refugees from Africa, in response to sectarian violence, persecution, famine and human trafficking. Alehegne was one of 820 Ethiopian refugees who arrived in the U.S. in 2012, up from 594 in 2011. He would have undergone an intense screening process to be accepted into the refugee program.

“There’s a screening process, fact-checking, and corroborating people’s identities,” said Chris Boian, spokesman for the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees in Washington. All who enter a refugee camp have to undergo an exhaustive series of interviews — including psychological screenings — to determine whether they will successfully assimilate into a new host country.

Vetting process

“It’s a constant process of prioritizing and looking for the very most vulnerable individuals,” Boian said.

Only after completing that screening process could Alehegne have applied to resettle in the United States, at which point he would have had to pass security checks, an in-person Department of Homeland Security interview and a medical exam.

Photo: Sarah Rice, Special To The Chronicle

Mourners watch as an Ethiopian flag is hung on a telephone poll in Oakland at a vigil for Yonas Alehegne, a refugee who suffered mental illness and spent time at San Quentin before being fatally shot by police.

Esayas Gezahegne, an Ethiopian refugee who works for the nonprofit Horn of Africa Human Rights Network in Oakland and is familiar with the screening process, said Alehegne could not have passed had he shown signs of a mental illness.

“I’m quite sure no,” he said.

Life in America

According to probation reports, Alehegne touched down in New York in 2012 but left almost immediately for Kentucky, where he lived with a friend while working short-term jobs as a parking attendant and custodian. He obtained a residency card during that time and worked at a Walmart in 2013, according to his former attorney Randy Baker.

Yet, better employment evidently didn’t beget a better life. After Alehegne resettled in the United States, he routinely sent money home, Alemu said, but his mental health began to deteriorate. Baker said Alehegne saw several doctors who said he suffered from mental illness. But Alehegne told probation officers that he couldn’t recall the diagnosis, and never took medications to treat it, Baker said.

He moved to the Bay Area in 2014, unemployed and on his own. And he quickly ran into trouble that summer when four men beat him up on a street and broke his nose. He was staying in a respite wing of the East Oakland Community Project homeless shelter that August, healing from the attack, when, according to authorities, he followed a shelter employee into a bathroom she was cleaning and began undoing his pants, yelling at her to “shut up.” She screamed and others came to her aid, but later that night, Alehegne followed her into and through a BART train, laughing at her distress, authorities said.

Alehegne was arrested and convicted of threatening and stalking the woman, then sentenced to 16 months in state prison.

Photo: Sarah Rice, Special To The Chronicle

Fikre Atnafe lights candles at a vigil for Yonas Alehegne, an Ethiopian immigrant he knew who was shot and killed by an Oakland police officer in August, in Oakland, Calif., on Sunday, September 13, 2015.

Alehegne’s English was so limited that on the day of the offense, an interpreter had to tell him he’d been kicked out of the homeless shelter. Another shelter resident, Vernon Wiley, would testify in court later that Alehegne tended to mimic “jibber jabber” he heard on the radio, but couldn’t communicate beyond that.

“He may not have had the wherewithal to access what services we have,” Charles Jameson, the Oakland attorney who represented Alehegne, said.

On the streets

Alehegne served time at San Quentin State Prison and was released in May, having served only part of his sentence. By then he had become increasingly addled, said Fikre Atnafe, another Ethiopian immigrant living in Oakland who saw Alehegne hanging around Lake Merritt shortly after his release, and tried to help.

“He was on the streets, Atnafe said, adding: “He was extremely traumatized by the police.”

In July, an Oakland police officer found Alehegne plucking the feathers from a decapitated goose by Lake Merritt. Alehegne told the officer he was hungry and intended to eat the goose. The officer stunned him with a Taser after Alehegne refused to obey commands.

He was sent to John George Psychiatric Hospital in San Leandro for an evaluation, then transferred to Santa Rita Jail, charged with cruelty to an animal and resisting arrest.

“You gotta know, this guy came from a different part of the world,” Atnafe said, suggesting that Alehegne’s mental illness, compounded by a language barrier, invited misunderstanding.

Calls to his parole agent were forwarded to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. An agency spokesman declined to comment.

A small vigil

Photo: Sarah Rice, Special To The Chronicle

Ash Gichamo speaks at a candlelight vigil in the spot where Yonas Alehegne, an Ethiopian immigrant, was shot and killed by an Oakland police officer in August, in Oakland, Calif., on Sunday, September 13, 2015. Gichamo didn't know Alehegne but says there's a lot of Ethiopians in that neighborhood. "It could have been me," he said.

On a recent Saturday, Atnafe joined about two dozen other people for a vigil in memory of Alehegne. It was held at Van Buren Avenue and MacArthur Boulevard in Oakland, near the laundry room where Alehegne slept.

Atnafe hung an Ethiopian flag on a telephone wire and lit candles beneath it as others passed out slices of spicy anebabero bread to commemorate the New Year.

The vigil’s organizer, Ash Ashebe, passed out flyers with Alehegne’s photograph. It showed the man with a long, narrow face and searing brown eyes who came to the United States for refuge and wound up dying in the street.

For now, his remains are being held by the Alameda County coroner’s office. But Benyam Mulugeta, board president of the Oakland’s Ethiopian Orthodox Church, believes it isn’t too late to grant Alehegne’s last wish: to go home.

Rachel Swan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. E-mail: rswan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @rachelswan

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)