Students enrolled in service learning courseIL 152 International Human Rights/PO390 Politics Seminar recently hosted a “Free Dr. Gerba Week” to illuminate the plight of Scholar At Risk (SAR) Professor Bekele Gerba and his situation in Ethiopia.

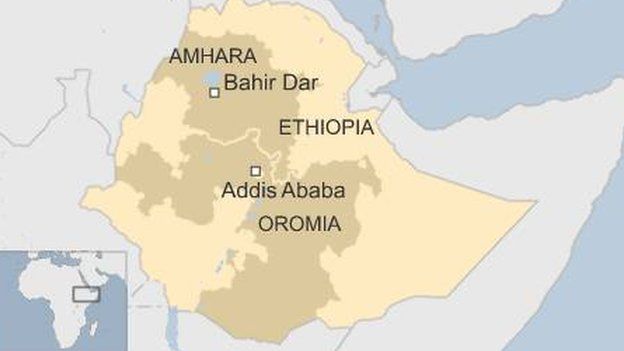

Students of Dr. Janie Leatherman, professor of politics and international studies and Dr. Alfred Babo, sociology and international studies professor, have taken up the case of Professor Bekele Gerba, a foreign language professor at the University of Addis Ababa. At the time of his arrest, Dr. Gerba held the position of First Secretary General of the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), a political party. He is a nonviolent activist, who has promoted nonviolent action and translated materials on nonviolence, such as by Martin Luther King.

Free Dr. Gerba Week kicked off with a Snapchat takeover, a #Free Gerba photo booth and Ethiopian food. Day two featured a student panel in Loyola followed by a research symposium in the library. A petition was made available throughout the week which concluded with a cupcake give away.

Dr. Leatherman said Fairfield students’ advocacy efforts have helped to bring international attention to Dr. Bekele Gerba’s case. “Students were successful in raising student awareness on campus about rights to education and freedoms necessary to exercise it, such as freedom of speech.” Dr. Janie Leatherman continued, “The CT Post's coverage of their campaign was also instrumental in spreading awareness not only locally or state-wide but also internationally.” That article was republished in Europe and Ethiopia press, and via other major African news sites.

Through advocacy work and while examining basic human rights, philosophy, principles, instruments and institutions in a global context, students have learned about human rights abuses in Ethiopia and Dr. Bekele Gerba’s case, specifically the mistreatment of the Oromo people, Gerba’s leadership of their nonviolent movement and more recent episodes of oppression and killings by the government. The research they have conducted for Scholars at Risk includes a background on the history and government of Ethiopia, its current geo-strategic relations, foreign policy, domestic politics, and other concerns, such as the famine Ethiopia currently is facing in parts of the country.

Students are preparing an advocacy report on Dr. Gerba that will assist Scholars at Risk in its work to highlight his case internationally, advocate for him, and endeavor to protect his human rights and ultimately secure his release and safety. Through this process, students gain skills in research, writing, communication, teamwork and advocacy, and a specialized understanding of human rights violations in the context of higher education.

The students have carried out research on four stakeholders: UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the US Department of State's Bureau of Human Rights, Democracy and Labor, the European Parliament and the African Union.

Last year, Dr. Leatherman and her students were asked by Scholars at Risk to help work on policy research surrounding the case of Dr. Mohammad Hossein Rafiee, a retired Iranian chemistry professor, who had been imprisoned in Tehran. His case that was fraught with layers of complexities, decades of sanctions on Iran and the nuclear accord. In September, after spending 15 months prison, Dr. Rafiee was released on medical furlough and was allowed to recuperate at home, without guards. Scholars at Risk Advocacy Director, Clare Farne Robinson said Fairfield’s research and advocacy were “instrumental in moving Dr. Rafiee's case forward.”

Recognizing the efforts of Dr. Leatherman’s and Dr. Babo’s students on behalf of Dr. Gerba, Robinson said, “I have been thoroughly impressed with the students' commitment to this case, the leadership they've demonstrated in their actions, and their creative advocacy.”